- Home

- Christy O'Connor

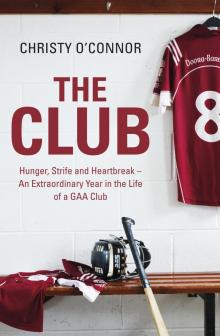

The Club

The Club Read online

The Club

CHRISTY O’CONNOR

PENGUIN IRELAND

PENGUIN IRELAND

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 2010

Copyright © Christy O’Connor 2010

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-14-196521-5

To Róisín O’Connor and Ger Hoey

Contents

1. Doubts

2. Make or Break

3. Róisín and Ger

4. Down to Business

5. When We Were Kings

6. The Future

7. Let’s Get It On

8. Crossing the ’Bridge

9. Going Down

10. Pain

11. Return of the Man

12. Let the Healing Begin

13. Top Dogs

14. The Red Lad

15. White Fluffy Clouds

16. Passion

Acknowledgements

Photo Credits

1. Doubts

From 70 metres away, even against the blinding rays of the sun, I can see their midfielder arch his body back on the turn. He is leaning so heavily on his right leg that it’s almost possible to observe a pirouette in the manner of his address. I know that his attempt at a score from that distance isn’t going to have the legs to carry over the bar. He gets a clean strike, but the ball has a lower trajectory than normal and it’s drifting, hanging, teasing in the air. That means one thing: danger.

Their corner-forward has got goal-side of our corner-back and is tracking the flight path of the ball like a hawk closing in on its prey. I’m fully focused on the ball but I can see him out of the corner of my eye, and now I can hear him charging like a rhinoceros, which further heightens my awareness of the threat. I know I’m probably outside the square, which removes any protection I might get from the referee or umpire, so that leaves only a split second to decide how to deal with this situation.

I’m already on a yellow card for railroading the same player in the first minute when he was straight through on goal, but I don’t have time now for my brain to compute the ramifications of another reckless challenge. I can only worry about the ball, because there’s nobody else behind me. I should probably bat the ball away to limit the danger but I’m confident in my handling and my mind is made up in a millisecond. I decide I’ll take it at its highest point by out-jumping the forward and fielding the ball over his head and above his reach.

Bad decision. The ball loops that bit lower than I anticipated and he gets the gentlest of caresses on it. I don’t know whether it has glanced off his hurley or his arm, but it’s not in my hand. I don’t need to look behind me to know where the ball has ended up because I can hear the forward’s shriek of elation before the roar rises up from the belly of the crowd. The ball has just crept beyond the line and is nestled in the bottom right-hand corner. Another half a foot and it would have been outside the post, which is almost like another slap in the face.

Frantically, I opt for Plan B, something every goalkeeper has in his bag. ‘SQUARE BALL! Ah, come on, umpire, he was definitely inside in the square. He was all over me.’

The umpire doesn’t entertain my plea for a second. He’s already reaching for the green flag. But this is more than just a goal. It’s like a dagger in our hearts, a mortal blow to whatever chance we had in this game.

The timing is critical. As soon as I puck out the ball, the referee blows the half-time whistle. I glance up at the scoreboard behind me and there is the harsh reality, staring at me in big bold letters and numbers:

Newmarket-on-Fergus 1-8

St Joseph’s Doora-Barefield 0-2.

As I pick up my hurleys and bag from the side of the net, the agony of the goal is tearing up my mind and I silently and angrily mutter words that seem vulgar, obscene and selfish in the context of a hurling match: ‘Jesus Christ, why did you do this to me?’

It makes no sense – but right now nothing seems to make sense.

They’ve scored 1-8, and we’ve had to save a penalty and survive some manic goal-line scrambling. They’ve decoded our puckout strategy and have gone a long way to shutting it down. Our defence has played some heroic stuff but it’s being slowly suffocated by the pressure originating higher up the field where our midfield and half-forward line are being annihilated. And on a dry and sunny October Sunday, in a county senior hurling semi-final, before a crowd of around 6,000, we’ve managed to score just two points in 32 minutes. This is embarrassing. This is wrong. All wrong.

Trailing by just six points at the break might have given us some hope to cling to, but the goal has killed any optimism. Our legs are weak and we’ve been stumbling. All through the half, we knew we were just one haymaker away from hitting the canvas. And now, they’ve just landed it on our chin.

The dressing room is mayhem. Guys roaring and shouting at one another, leaving little or no opportunity for critical assessment as to how we can somehow retrieve this situation. I walk through the shower area and into the adjoining dressing room to change my under-armour garment and to try and clear my head. Our corner-back, Marty O’Regan, follows me in. He doesn’t seem to know where he’s going.

‘Are you all right, Marty?’ I inquire.

‘I’m seeing double,’ he responds.

He’s been our best defender all year but he’s just been destroyed by their corner-forward, Colin Ryan. Now it makes sense. He took a sickening hit in the first couple of minutes.

‘You’re concussed, man,’ I tell him. ‘This game is over for you.’

Marty lies upon the physio table, while I just sit down and observe him staring vacantly at the concrete ceiling that is carved out of the seat indentations from the stand above us. Normally, you can hear the hum of the crowd and the Irish music playing from the tannoy, but today there doesn’t seem to be any sound. It’s almost as if this nightmare is happening while we’re suspended under water.

As our physio, Eugene Moynihan, tends to Marty, I can hear more roaring and shouting in the next room. As I make my way back in, two of our substitutes, Fergal O’Sullivan and Eoin Conroy, have taken over the floor.

‘What had we spoken about beforehand?’ roars Sull. ‘We said we’d get in their faces and drag them into the trenches for a bat

tle. And we’re just letting them walk all over us.’

Conny was more personal. Their full-back and centre-back have been dominating, so he takes aim at Noel Brodie and Seánie McMahon, our centre-forward and full-forward.

‘Will ye at least stand down on top of those two fuckers. They’re outside there doing what they like. Walk down on top of them. Start a fucking brawl if ye have to. Grab one of them by the throat, but do something to stop them waltzing out with ball after ball. AND GET INTO THE FUCKING GAME.’

Our management, though, seem to have just accepted the inevitable. ‘Whatever about the result now, I want ye to go back out and at least show some pride in the second half,’ says our coach, Seán Chaplin. ‘What we’ve shown is just not good enough. We need to go back out there and not lie down like we have done in that last 30 minutes.’

Those words don’t appear to have reached us, but I doubt if any words can pierce the layer of doom that has enveloped the room. Then Seánie McMahon stands up and begins to talk loudly and assertively, spittle almost splattering from his lips. This is a man who effectively launched the Clare hurling revolution in 1995. With Clare trailing by two points to Cork deep in injury time of the Munster semi-final, McMahon, withered from pain after breaking his collarbone, somehow engineered the sideline cut which led to Clare’s match-winning goal.

To him, nothing is impossible. ‘Fuck that shit about going out and fighting for pride. I’m going out in the second half to win this game. We’re nine points down but we haven’t even started to hurl yet. We’ve been asleep for 30 minutes, but if we wake up, this game is still there for us. If we get a goal, we’ll put them under pressure. And if we get a run on them, these boys will fucking collapse.’

Seánie’s voice has jolted us from our seats and got us back up on our feet. This is a time to see who cares and how deeply this all matters. Time for all of us to give something.

But as we gather in a huddle, arms wrapped tightly around one another, the soundtrack still doesn’t seem convincing. Looking around the huddle, there is enthusiasm and hope, but you know it’s false. There are too many blank stares and stooped shoulders, too many faces mirroring anxiety and confusion and an unmistakable vulnerability. You can sense the doubt, almost feel the fear.

We know. We just know. We can feel it. A forest fire of aggression won’t be enough to burn Newmarket because they’re playing at a level way above us. Half-time has only been a respite from the barrage they have already hit us with and it’s inevitable that the agony will soon start again. In hurling, nine points can be erased with three pucks of a ball, but doubt appears to have taken a crippling hold of our collective consciousness.

They hit us hard again just after the break. Bang, bang, bang. We respond with a goal, but their scores are coming more frequently now. Each score is now like an accurate jab which thuds home even harder than the last.

We have no real history with Newmarket, but they’ve got a real run on us and they seem to have just decided that they’re going to slay us. The last ten minutes are agony. Two late goals draw some audible cheers from our supporters, but they arise from loyalty rather than from any hope or satisfaction.

Newmarket-on-Fergus 1-20

St Joseph’s Doora-Barefield 3-7

The final winning margin is only seven points, but that doesn’t conceal the reality that this was a total rout. Annihilation. We may have scored 3-5 in the second half, but it felt like a training run for them ahead of the county final. For Christ’s sake, they gave a rake of their young subs a run in the last quarter.

As I make my way off the field, they’re heading for the bottom corner to complete their warm-down. I walk straight into the middle of their pack and shake hands with as many of them as I can. Their manager, Diarmuid O’Leary, who I hurled with in St Flannan’s College, seeks me out. I shake his hand, pat him on the cheek and wish him all the best for the final.

Then their coach, Ciaran O’Neill, makes his way over. Most of us played alongside O’Neill with Doora-Barefield. He was one of our great players and he even managed us for one season. But he coached Kilmaley to beat us in the 2004 county final by a point, and now he has helped another team to obliterate us. We shake hands but no words are spoken. No need for them now.

Before I make my way to the dressing room, I wait in front of the tunnel on the halfway line for their captain and goalkeeper, Kieran Devitt. He is talking to friends, but then he spots me and ambles over.

‘Just one of those days,’ he says. ‘One of those days when nothing went right for ye.’

In the last 15 years we have played in ten Clare senior hurling semi-finals; now we’ve just lost our fourth. One of those defeats, against Éire Óg in 2000, was one of the most sickening losses we ever experienced, because a vastly inferior team out-fought us to end a two-year undefeated run in Clare and Munster. That was low stuff, but this is nearly as bad because Newmarket have done more than just beat us: they’ve shredded the name of this team.

We really believed we could win this county title. We’re short of young talent and this team doesn’t have the same positive age profile associated with most emerging teams in Clare. But we felt that our physique, experience and fireproof belief might be enough to take us there. Plus, we’d been backing it up, coming into the game; in our five previous championship matches, we’d averaged a score of 1-18 and had only conceded an average of 0-12.

We came into this semi-final with perhaps a 50–50 chance of beating a young, highly talented, extremely mobile, hungry and motivated outfit. We felt that we had the men for the big day and they hadn’t, and if we could drag them into a battle we’d be the only ones left standing at the end of it. Now that assessment must be subjected to serious re-evaluation.

In the dressing room before the game, the last words in our huddle were delivered by Davy Hoey. One of our best and most experienced defenders, he was out injured after almost losing a finger in a work accident four days earlier.

‘My heart is broken that I can’t go out there with ye,’ he told us. ‘I can hardly speak because I’m fighting back the tears. But I know ye’ll do everything ye can to try and help me make up for the disappointment I’m feeling. The whole county is going on about Newmarket and their royalty and their place in Clare hurling. They’re all saying that the Blues are back, that they’re going to start dominating Clare hurling again. Well, fuck the Blues. We’ll show them what championship hurling is all about. We’ll fucking eat them alive.’

Those words seem hollow now. They physically dominated us and they got the scores whenever they wanted, safe in the knowledge that we were incapable of being anything more than a temporary irritant.

As a team, it’s been a long time since we were a dominant force; but we were never rolled over in senior hurling like we have just been. In the last 15 years, the heaviest defeat we ever suffered in a big championship game was an eight-point loss to Wolfe Tones in the 2005 semi-final. And they got a goal deep in injury time of a match that was still in the balance up until that point.

This was a wipe-out. We were slapped around and we went down ugly. But the most worrying aspect for the future was what I saw at half-time. Although fear is the opposite of confidence, fear can sometimes be a positive thing in a dressing room. It focuses minds, drives some players to greater lengths, makes more players obsessive in their pursuit of victory. But that wasn’t the type of fear I saw in the huddle; I saw anxiety, trepidation, almost an acceptance of defeat. In 19 years as St Joseph’s Doora-Barefield first-choice goalkeeper, that was something I had never witnessed in a senior dressing room before.

After a meal at the Grove bar in Roslevan, I drop Seánie McMahon home. As we make our way along the Tulla road on the way to Spancilhill, the discussion inevitably drifts back to half-time.

‘Fair play to you for what you said but, Jeez, I never saw as much doubt from some fellas in a Doora-Barefield dressing room in all my life,’ I say to him. ‘I knew we were fucked in the second half.’

As we turn left at Spancilhill Cross, I pose the inevitable question.

‘Well, is that it? Will you be back?’

Still obviously disappointed with the performance, Seánie’s voice is tinged with sadness.

‘I don’t think so, boss. I can’t see it, anyway. I’d say that’s it.’

He and his wife Mary have three young boys now. Bedtime for them is normally between 8 and 9.30 p.m., which puts a real burden on Mary on the nights we train.

I have played alongside Seánie with Doora-Barefield since we were both nine years of age. The two of us have never known anything different, but there comes a time when family has to take precedence over hurling.

If today is to be our last day together as hurlers, the saddest part of the ending is that, unlike the really great days, we couldn’t find an ember in our collective heart to stoke the fireplace in our souls and get it raging again. But as the boys of summer grow into the old men of winter, at least we will always have those treasured memories of when we hurled together.

Outside Seánie’s house, we clasp our right hands tightly together.

‘If that’s it,’ I tell him, ‘I just want to say that they were the best years of our lives.’

‘No doubt about it,’ he responds. ‘The best years of our lives.’

I turn the car and head for home, empty and low. Maybe today was just one of those days and we’ll all come back stronger and hungrier than ever next year because of what just happened. You try and suspend that doubt and disillusionment because you don’t want to admit that this show could be over.

But maybe it just is.

2. Make or Break

Before 2009 even began, the word on the ground was that we were already in danger of being ripped apart. Or even tearing ourselves apart. Two guys were going head to head for the senior management job, one of whom had two sons on the team, and the fallout could sunder our season before it even began.

The Club

The Club