- Home

- Christy O'Connor

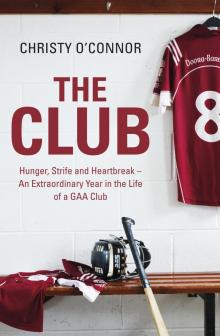

The Club Page 2

The Club Read online

Page 2

At the end of November, I got a call from Tommy Duggan, the club chairman. I had been U-21 manager for the previous two seasons and he asked me about staying on for a third term, but I had to turn down the request for personal reasons. After a brief discussion about potential candidates, the name of Patsy Fahey, a recently retired player, came up.

When Duggan rang Patsy about the U-21 job a couple of days later, he also threw it out there that they might be looking for a new senior management because our coach, Seán Chaplin, was leaving us to join the Sixmilebridge management set-up. When Patsy expressed some interest, Duggan explored the possibility of him getting involved in some capacity.

As chairman, it would have been foolish of Tommy Duggan not to pursue Patsy, because he had been building an impressive CV as a coach outside the club. In 2007 he coached Corofin to a Clare county quarter-final, which was a massive achievement for that club. Then last year he took Gort to their first county senior final in Galway since 1983. They lost to Portumna, but they’d been level with them at half-time and their performance reflected a smartly coached and well-drilled side. He’d been double-jobbing all season, as he’d remained with Corofin, but he stepped down from that post after the championship. And since he hadn’t been given any guarantees by Gort that he’d be going back there, the prospect of managing his own club’s senior team suddenly loomed into view.

Patsy told the chairman that he’d think about it on one key condition: he didn’t want to be incorporated into the existing management. If he was taking over, it was on his terms. He said that he’d be back with an answer within the week.

The possibility of removing the remainder of the management team was always bound to cause friction. They had taken us to a county semi-final just two months earlier, while Kevin Kennedy had also helped steer the club through a crisis just five weeks before the start of the 2007 championship when recruiting Chaplin as coach. Kevin was a massive clubman and he had two sons – Ken and Damien – on the panel; their allegiance was inevitably going to rest with their father. Moreover, both were extremely popular players in the club and were a central part of the senior team. In their eyes, and their father’s, the only outstanding issue with regard to management was recruiting a coach, because everything else was in place.

Three days before the club AGM on 15 December, Patsy informed Tommy Duggan that he would take the job. Tommy subsequently rang Kevin, thanked him for his services, but told him that they were no longer required. Then all hell broke loose.

The following day, Eoin Conroy rang me. Ken Kennedy had just been on to him and was raging at how his father had been treated. Conny was siding with Ken. ‘It’s been handled badly and the boys have a right to feel aggrieved. They’re not happy, and neither are some of the other players. And Ken asked me to ring you to find out where you stand on all of this.’

‘Sure you know where I stand,’ I said back to him. ‘And Ken knows that as well.’

Patsy was a good friend of mine, and it was almost impossible for me to portray myself as neutral in this debate. But as far as I was concerned, personal relationships didn’t matter here: Patsy was primarily a coach, while Kevin was a manager, and it’s always far harder to get a good coach than a manager at club level.

The ideal situation would have been for the both of them to work together – which would have suited everyone – but Patsy had emphatically ruled out that possibility. As a player under Kevin’s management, Patsy had history with him and had no desire to work alongside him now.

When I arrived outside Fahy Hall, a local community centre, for the club AGM that Sunday, the first person I met was Ken Kennedy, who was getting out of his jeep. ‘What’s gone on over the last week is a disgrace,’ he said. I couldn’t really engage with him because he knew that my support would be with Patsy in this debate.

The meeting was supposed to begin at 4.30 p.m., but it didn’t begin until 4.45 p.m.

Kevin Kennedy wasn’t present. Patsy arrived in at 4.50 p.m. and sat in the front row – you couldn’t miss him because he was wearing his bright orange Denver Broncos jacket. He was sitting just feet away from the club’s three executive members – Tommy Duggan, Secretary Dan O’Connor and Treasurer Martin Coffey. The only trophy the club had won last year – the U-21A football cup – was placed on their table.

When it came to the team management reports, the only one present from the senior team was Fr Michael McNamara, who’d been a selector for the previous two seasons. He hadn’t anything prepared, so he just gave a brief synopsis of the year off the top of his head; then he headed off to say evening mass.

When it came to the appointment of the senior team management, Tommy Duggan said that the club had decided to ask Patsy to take over. And that he’d accepted. And then the inquisition began.

Pat Frawley, one of the club’s county board delegates, asked why the previous year’s management weren’t considered. He highlighted the good season they’d enjoyed and he proposed that they be put back up for ratification. He was seconded by someone from the floor, and suddenly the meeting took on a totally different mood.

Tommy Duggan outlined how Seán Chaplin was not staying on as coach and how that had necessitated the trawl for a new management ticket. Marty O’Regan, corner-back on the senior team, then asked the top table about the make-up of the new management team; Patsy said he hadn’t assembled it yet. He’d only decided to take on the job that week and said that he hadn’t had time to approach anyone. All he knew was that if he was given the job, it would form a joint ticket with the U-21s.

Cathal O’Sullivan, the team captain, then spoke up. ‘I’ve been speaking to the players over the last few days and we want the club to hold off on the appointment of a senior manager until both parties reveal the make-up of their backroom teams.’

Although Patsy had played with almost every player present in the room, it was obvious that he didn’t have universal support among his peers. That was hammered home by Damien Kennedy, Kevin’s son. ‘The club dropped a bombshell on Thursday night and it’s not acceptable the way it was done,’ he said. He thought the players needed time to absorb what had happened.

The chairman was clearly annoyed with Damien’s response. ‘There was no bombshell dropped on Thursday night and there was nothing underhand about how it was done,’ he replied. ‘We’ve all seen in the past how hard it is to get a good coach. We have an excellent coach on our doorstep and I felt I had to act quickly to try and get him for the senior team. I felt if I hadn’t, Patsy might have been snapped up by another club, and we’d be trawling the county for a coach. And we’ve seen in the past how hard that can be and how long it can take.’

But Tommy was still on the back foot and there was clear support for Kevin all over the room. No one had offered a single show of support for Patsy. I decided to speak up.

‘Look,’ I said, ‘as far as I’m concerned at the moment, the Under-21s are the most important appointment we’re going to make here this evening because their campaign is beginning in March and we need to get that management in place. We have won one Under-21 championship game this decade and that group has to be our priority for the moment. We’re not going to get a better coach than Patsy for our Under-21s, but I’m just wondering – if Patsy isn’t appointed as senior coach, does that mean he’s not going to take the Under-21s? Forget everything else for a moment; that needs to be clarified straight away.’

Patsy addressed it immediately.

‘I haven’t my mind made up yet but I probably won’t take the Under-21s if I’m not over the senior team. I’ve heard a couple of rumours that another club [in Clare] were going to approach me. And if I’m not with Doora-Barefield, and am with another club, I’ll probably take their Under-21 team as well. That’s what I did with Corofin because it provides a good link between the Under-21 and senior teams. And if I’m with another Under-21 team, I can’t really take the Doora-Barefield Under-21 job.’

You could have argued that Patsy was using th

e U-21s as a weapon but that’s not his style, and his point was valid. Because if he wasn’t with us, he was definitely going to be snapped up by some other club in Clare. Either way, it was clear that any decision on appointing a manager couldn’t be taken this evening.

After another ten minutes’ debate on the subject, it was decided that both candidates – Kevin and Patsy – would assemble their management teams over the next three weeks and the club would convene again on 5 January, when the managerial appointment would be decided by a vote.

After the meeting, I approached Cathal O’Sullivan, the team captain, in the car park. ‘When you were articulating your view, which I respect, you said that you had been discussing the issue with the players,’ I said to him. ‘Well, you didn’t say anything to me.’

‘I thought Ken had contacted you,’ he responded.

‘No, he didn’t.’

It was obvious already that a split was developing in the panel. We’d been down that road before, in 2003, when Kevin went for the job against Ciaran O’Neill, who had only retired as a player at the end of the 2002 season. Half the players wanted Kevin, while the other half wanted O’Neill. At the AGM, Kevin was proposed and seconded by Mikey McNamara and Ollie Baker, two highly respected figures in the club, and he won the vote.

We didn’t get out of the group that year, and the following season Kilmaley beat us in the county final with a team coached by O’Neill. To this day, there’s still some bad blood in the club over that split. The last thing we needed now was more division. We were fragile enough. Another split could finish the team.

*

The GAA has a complicated, umbilical relationship with the community around it, and the club is a forum for magnifying the experiences of local life. It is largely a coalition of friends, neighbours, blow-ins and recruits, but sometimes the club is a magnet for resentments and arguments.

My relationship with Kevin Kennedy goes back a long way. I played with him on the club’s first team when I was only starting out and he was coming to the end of his career. I always had great regard for him because he was an unbelievably genuine hurling man. He played the game for as long as he was able to, and he finally packed it up in 1996 only after he had fulfilled a long-held ambition of playing alongside his son, Ken. A year later he managed the Clare minors to the 1997 All-Ireland title, and when he went for the club senior job at the end of that season I voted for him in a head-to-head with Michael Clohessy. Claw went on to become the most successful manager in the history of the club.

Louis Mulqueen, who trained us to the 1999 All-Ireland club title, had been recruited by Kevin in 1997. Even when he wasn’t involved during the glory years that followed, Kevin was still heavily linked to the team and he never wanted anything but the best for us. He’d be there, carrying hurleys or water bottles, always offering us support and advice. At the end of the 1999 All-Ireland club semi-final against Athenry, he was the first man I met on the field after the final whistle because he was down behind the goal with a batch of sticks. If you look at the video, you can see the two of us rolling around Thurles, him on top and me hardly able to breathe with the weight from his large frame.

He had an excellent record as an underage manager and he managed us to the Clare Cup (league) title in 2003. We had a load of injuries that season but I still felt that we needed to change direction afterwards. It was nothing personal, just hard-headed business. At a players’ meeting at the end of that season, I stood up and said that he should go. It was an extremely difficult decision, especially with his two sons on the team, and I wonder if the lads have ever really forgiven me for it. Sometimes, the pursuit of success can be blind and damaging, but I was prepared to accept the pain at the time in the hope of the pleasure of success down the line with a new manager.

We’ve consistently had our differences ever since. After last year’s group game against Tubber, we exchanged words. There was a cooling-off period between us for two weeks before the quarter-final. Then after we whipped Inagh-Kilnamona in the quarter-final, he came over and shook my hand in the dressing room and I just smiled at him.

Ten days later, the man proved that he’d do anything for you. The Tuesday before we played Newmarket in the 2008 county semi-final, my puckout hurley was stolen during a training session in Roslevan under lights. I left it down on the side of the pitch and a few young lads from the town made off with it. Paul Hallinan, one of our young hurley carriers, knew one of them, but he wasn’t sure if he had taken it. I was like a lunatic: a goalkeeper often sees a puckout hurley like a favourite snooker cue and I needed mine back. Kevin is a detective in Ennis Garda Station and he was the obvious man to go to.

‘I need that stick back,’ I said to him.

‘Leave it with me; I’ll see what I can do.’

The following day, I got a call from a private number around 4 p.m. It was Kevin. ‘Good news. I’ve got your hurley.’

He probably had the forensic squad out looking for it all day. ‘I owe you one big-time,’ I said to him.

His response summed him up. ‘All I want is a win on Sunday.’

Kevin has massive experience from managing Clare minor, U-21 and intermediate teams and he is a hugely popular figure, both inside and outside Clare. Many people within the club wanted him to get the job because of his huge historical connection to St Joseph’s. His two grand-uncles played hurling for the parish team in the early part of the last century. In 1970, Kevin won a Junior League medal with the club as a 16-year-old alongside some members of the St Joseph’s county title-winning team from 1958. Before he retired, he had also played alongside many of the players who won the club’s next county title, in 1998. That’s how strong his link is with the club. Fr McNamara, a selector in 2008, has also committed to joining Kevin’s team in 2009, further strengthening his candidacy. With all of that going for him, there’s no doubt that he’s going to get a lot of votes on 5 January. Conny and I were in town just before New Year and we ran into a clubman, Justin O’Driscoll, in the Temple Gate Hotel. He said that Patsy would be better off not turning up because he felt Kevin already had it wrapped up.

Meanwhile, Patsy was gradually putting a decent package together. Brian O’Reilly, a respected fitness coach, had agreed to join him as physical trainer, while John Carmody, who had managed Kilmaley to the 2004 county final, was also part of his ticket. So was Steve Whyte, a former player.

It didn’t seem to be enough, though. Even though the manager’s job was set to be democratically decided, there were rumours floating around that if Patsy won the vote, four or five players were not going to play under him in protest. I didn’t know if those rumours were true, or if they were just released as a scaremongering tactic to sway some floating voters, but it was a concern. It didn’t matter who won the vote, we couldn’t afford to allow that kind of insidious negativity to grab us by the throats and choke the life out of the spirit we’d built up in 2008.

Over that weekend before the vote, moves were made behind the scenes to get Patsy and Kevin to team up together. Kevin was prepared to go with it, but Patsy wasn’t prepared to work with Kevin. And anyway, he had expended enough time and energy in assembling his backroom team – he had asked 14 people before getting his first positive response – and he wasn’t prepared to let those people down, now that they’d committed to him.

On the Sunday night, Tommy Duggan rang Kevin to ask if he’d finalized his backroom team, and Kevin said that all would be revealed the following evening. That was a concern to the club executive, because they weren’t sure if Kevin was recruiting a coach. And if he was, would that coach be looking for expenses?

At 6.15 the following evening – the meeting was due to begin at 8 p.m. – Cathal O’Sullivan, the team captain, rang me. He said that Kevin had got a coach. He was a very respectable name who had huge experience. It was a positive move for Kevin, but I wanted to broach a totally different issue with Cathal.

‘Look,’ I said to him, ‘it doesn’t matter who gets t

he job, but I’m sure you’ve heard these rumours about some lads not playing if Patsy gets the job. That’s pure bullshit. No matter who gets the job, we all have to row in together. If we don’t, we’re totally fucked. And you’d better call every player together before we go into the meeting tonight and re-emphasize that point.’

I’d been elected vice-chairman at the AGM, but only to allow me to head up a new committee to look for an underage coach for the club. I made it clear that I’d no interest in getting involved in administration or politics and that I’d be going back to coaching underage teams next year. Given our poor underage record in recent years, getting a qualified coach into the schools was something that I’d been pushing for years. And at the AGM, it finally seemed to be getting the green light.

Because of my new position, I had to be at the Auburn Lodge Hotel at 7.30 for a meeting of the club executive before the main event. In the bar of the hotel, eight members of the executive were sitting on stools around two small tables, debating what might unfold within the hour. The club had more or less committed to financially backing the part-time appointment of a new underage coach, which would seriously impact upon its ability to pay a coach expenses for the senior team. Patsy had informed the club that he wouldn’t be looking for expenses to coach the team, but no one was sure if Kevin had discussed any arrangements with his prospective backroom team.

Joe McNamara, the club’s registrar, reminded everyone how strong the support was for Kevin within the parish. And no matter what happened now, the club would have to back him if he won the vote. Yet since Kevin was primarily running as a manager, he needed a coach. And if the club couldn’t afford a coach’s expenses, the knock-on effects were going to be huge for the players. Players rarely have any difficulty with a manager once they’re treated properly and the coaching is enjoyable and challenging. If it’s not, then the red flags go up.

The Club

The Club